Geffrei Gaimar and Wace of Jersey both extolled Alan’s prowess in the Battle of Hastings: Gaimar wrote that he and his men struck “like barons”, “they and the others struck so well that the battle was won”; Wace asserted that Alan caused the English “great damage”.

One has to wonder then why Alan is not mentioned by contemporary sources such as William of Poitiers (WP) or the “Carmen de Hastingae Proelio” attributed to Guy of Amiens. In fact, neither names any Bretons at all despite acknowledging that they comprised a large part of the army. Perhaps this is unsurprising as both had the aim of glorifying Duke William’s personal accomplishments. Moreover, WP expressed intense dislike for everything Breton, including private dairy farms, comparatively free relations between men and women, and the multitude of armed citizens.

Is there then no contemporary evidence of Alan’s participation in the Battle? Actually, there is, but to find it we need to trace back from Wace. What damage could Alan have done?

In the post on the Chanson de Roland, I mentioned that Alan received many of Earl Gyrth’s manors.

The American medieval historian Stephen Morillo wrote an article on the battle in which he adduced evidence that the English had been on the verge of winning as they placed great pressure on the Norman front line. He believed that Earls Leofwine and Gyrth were the commanders who led this attack, and that it was their deaths, and the ensuing loss of cohesion, that turned the tide.

Let’s turn now to the only pictorial record of the battle, the Bayeux Tapestry (BT). The scene where Leofwine and Gyrth meet their demise is a long one, framed on both sides by knights bearing white shields.

On the far right we see a rider on a black stallion confronting a moustachioed axeman in chainmail.

The rider’s shield has twelve black spots, presumably insignia of high rank because other riders have fewer spots or none, and in an earlier scene a commander, presumed to be Duke William, is shown with twelve spots and a large cross on his shield.

Based on Gaimar, Wace, Morillo and Domesday, the riders with white shields are Breton knights, and we can reasonably identify the four figures on the left of the scene above as (1) William de Braose, (2) a thegn (plausibly the royal thegn Almaer who is known to have served Leofwine and Gyrth, and who might be Almaer of Bourn, son of Kolswein, two of Eadgifu the Fair’s tenants who subsequently served Count Alan), (3) Earl Gyrth, and (4) Alan.

This scene is particularly detailed, as if based on the testimony of two or more eyewitnesses. Under the above interpretation, Count Alan is about to swing his sword as his stallion averts its head from Earl Gyrth’s axe blow; the thegn’s axe is broken as he notices William de Braose approaching stealthily on foot, about to plunge the tip of his sword into Gyrth’s back.

Swords were mostly used as Alan illustrates, exploiting their weight and momentum as a hacking or bruising weapon, but de Braose is demonstrating a technique used, in favourable circumstances, to break through chainmail.

Alan occurs many times on the BT; for example:

In Duke William’s palace, Earl Harold Godwinson is addressing the Duke ad pointing to either his brother Wulfnoth or his nephew Hakon (named by the Anglo-Saxon rebus below of the “Hackin'” man). Behind Hakon, and directly above the axe, is the captain of the guard, a spearman holding a shield identical to Count Alan’s: he is depicted with yellow hair shaved behind in the Norman fashion and is wearing an orange tunic with a yellow v-neck.

But if we have scanned the BT from left to right, then we’ve seen this figure before, as one of Duke William’s messengers to Count Guy of Ponthieu:

He is the tall man standing next to the famed dwarf Turold who is holding the horses’ reigns; and there is Alan’s mount, a black horse, a hand higher and more spirited than the bay stallion next to it. Here we can see that Alan’s tunic has a yellow belt and that he carries a sword as well as a spear; the sword is the same yellow colour as the one in the battle.

The messengers appear in every scene between this moment and Harold’s arrival in the palace, so finding them is an easy exercise for the reader. Then we see Alan guarding the rear of William’s army as it crosses into Brittany.

A word about the Breton-Norman War of 1064-66: Alan Rufus’s father Eudon I was a younger brother of Duke Alan III (998-1 October 1039/1040). Alan III was a Guardian of Normandy and died (allegedly poisoned) while besieging Roger I de Montgomery during the latter’s rebellion against the child Duke William. Eudon claimed the duchy of Brittany and ruled it until his nephew Conan II became too strong for him. In 1057 Conan captured Eudon and imprisoned him, chaining him to a wall. A long war between Conan and Eudon’s sons ensued. Eudon was eventually released but the conflict continued. Conan besieged Eudon’s vassal Riwallon, Lord of Dol, and Duke William, whom as we’ve seen Alan Rufus was already serving, went to Riwallon’s aid.

Howard B. Clarke, Emeritus Professor at University College, Dublin, identifies the figure seated and pointing next to Mont St-Michel above as Scolland, then head of illuminated manuscripts in the abbey’s scriptorium and later Abbot of St Augustine’s in Canterbury, where much of the Bayeux Tapestry appears to originate. I guess it’s more than coincidental that the steward of Alan’s Richmond Castle in the late 11th century was also named Scolland: the castle’s great Hall is named after him.

Here is Earl Harold rescuing two Norman soldiers who’ve got stuck in the quicksand as they cross the Couesnon River into Brittany.

Here is the relief of the citadel of Dol, with Alan Rufus in the rear of the army.

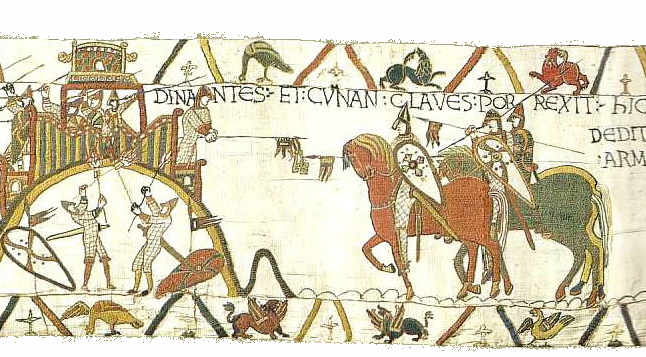

In armour now, Alan rides with William’s army to besiege Conan at Dinan.

Here, presumably, is Duke William II of Normandy, with his impressive shield, receiving the keys to Dinan from Duke Conan II of Brittany:

The Norman propagandists of course viewed this solely as a Norman victory over Conan, but we know better than that. Howbeit, William was impressed with Harold’s service, and knighted him:

William arrives at Bayeux. Hmm, who could that be riding immediately behind him on the black horse?

The infamous “Sir Harold, just hold your hands here while you swear an oath to me” scene:

Note that Alan Rufus is pointing to the word “sacramentum”, but Bishop Odo, scowling a little, appears to be shushing him.

Now, a word on the relationship between Odo and Alan. A charter by Eudon at Rennes dated circa 1050 was witnessed by “Viscount Robert and his brother Odo”. I believe these to have been the sons of Viscount Herluin de Conteville.

Conteville was the site of a shrine to the British Saint Samson of Dol, and was ecclesiastically under the governance of the Bishop of Dol. Moreover, Herluin was a name used by Counts of Ponthieu whose fastness Montreuil was occupied by British soldiers of the Roman general Magnus Maximus in 383 at the time when Brittany was founded.

Count Haelchod of Ponthieu provided a refuge against the Vikings for the monks of Landevennec in Brittany who founded a shrine to Saint Winwaloe at Montreuil. His son Count Herluin had complex diplomatic relationship with the Normans.

It’s a fair bet then that Viscount Herluin was of the family of the Counts of Ponthieu and that he had close links to Brittany, which would help explain why his sons Robert, later elevated to Count of Mortain, and Odo, who became Bishop of Bayeux, maintained such connections.

Having sworn to uphold Duke William’s claim to the English succession, Harold is permitted to take Hakon back to England with him:

It may be that Alan went to England at this time, for Domesday Book records that “Alanus” held Wyken Farm in Suffolk at the end of the reign of King Edward “the Confessor”. Many scholars dispute this, saying that “Alanus” must be a scribal error, but Wyken is in the parish of Bury St Edmunds and Count Alan was interred in the parish church graveyard by Abbot Baldwin, the royal physician for kings Edward and William.

And why wouldn’t Alan receive some favour from Edward? Eudon was an older maternal first cousin of Edward’s. Other continental figures associated with Alan also held land in England at this time: Robert fitz Wymarc was a relative of Alan’s, William’s and Edward’s ad was one of Edward’s trusted counsellors; Ralph the Staller, from Norfolk, also held lordships in Brittany and witnessed at least one of Eudon’s charters; Walter d’Aincourt, who remained a close friend of Alan’s for life, had property in Derby TRE (during the reign of King Edward).

All the BT lacks now is Alan’s name. Well, here is Edward’s funeral scene. Below his shrouded corpse walks a watchful animal. Some call it a dog (“King Edward’s pet dog?”), but leaving aside its strangely non-matching tail, it’s an elegantly drawn red fox.

Hmm. In the Norman palace scene with Hakon, the “Hackin’ man” is applying his axe directly below Count Alan. Isn’t this prescient of what later happens to Alan’s stallion? So not only Hakon, but also Alan, is associated with this English rebus. Could “the red fox” (the only one of its kind on the Bayeux Tapestry) be a rebus? Yes! It’s a Breton rebus for “Alan ar-Rouz”, that is “Alan Rufus”.

What’s happened to the fox’s tail? Instead of a magnificent red brush, it has a scrawny yellow thread. Two possibilities come to mind: a late haphazard repair, or a deliberate reference to Alan’s humiliation when, after Edward’s death, many of the continental landholders were stripped of their lands and titles.

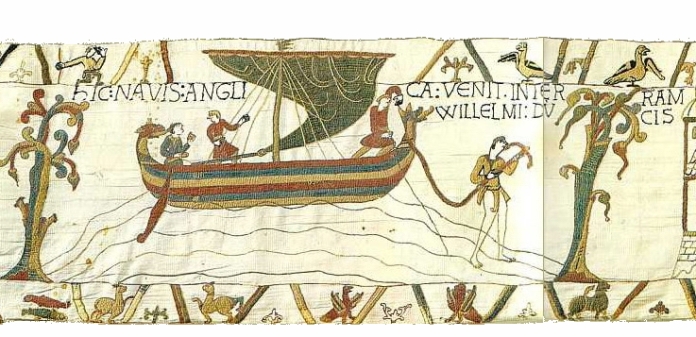

Speaking of those expulsions, I think this “English ship” arriving in Normandy may be carrying the exiles.

The date of this event is implied to be after the appearance of Halley’s Comet in England on 24 April 1066 which would explain why Alan Rufus missed the Council of Lillebonne.

Ejecting the Bretons instead of enlisting their support in the defence of England was not the new King Harold’s smartest move, for here they are returning in Duke William’s armada: note the ship with a griffin stern and two white shields in front of a dragon prow.

Alan appears in civvies again, as the man in the “Norman Last Supper” pointing at Odo’s name.

Alan might be depicted, as a knight in chainmail with white shield facing away as he rides on a black horse, in two or three scenes leading up to the fateful encounter with Earl Gyrth, but that’s less distinctive. Still, if we count the number of scenes in which we can be reasonably confident he does appear, it’s quite impressive.